On 16 January 1926, BBC Radio interrupted a broadcast of a speech from Edinburgh to give a special announcement: an angry mob of unemployed workers was running amok in London, looting and destroying everything in sight. Listeners were stunned. Anxiously they gathered around their radios as the alarming reports continued, informing them that the National Gallery had been sacked, the Savoy Hotel blown up, and the Houses of Parliament were being attacked with trench mortars:

The clock tower 320 feet in height has just fallen to the ground, together with the famous clock, Big Ben... Fresh reports announce that the crowd has secured the person of Mr. Wurtherspoon, the minister of traffic, who was attempting to make his escape in disguise. He has now been hanged from a lamppost in Vauxhall.

The news was accompanied by the sounds of a mob in the background and explosions in the distance. At this point some members of the audience began to panic. Listeners in London rushed out into the streets in an attempt to flee the city, while those outside the city phoned the authorities and newspapers to find out what was going on. Puzzled officials who swore that nothing was happening did little to placate the callers who swore back that something had to be occurring, because they had heard it on the radio.

The New York Times, January 18, 1926

Eventually, long after the situation had gotten well out of hand, the BBC eased tensions by reminding the audience that the events they had heard were part of Father Ronald Knox's comic skit titled "Broadcasting the Barricades" in which he simulated news bulletins about an imaginary "red riot." The BBC made the following announcement:

Some listeners, who heard only part of Rev. Father Knox's talk at 7:40 this evening, did not realize the humorous innuendoes underlying his imaginary news items, and have unease as to the fate of London, Big Ben and other places and objects mentioned in the talk.

As a matter of fact, the preliminary announcement stated that the talk was a skit on broadcasting, and the whole talk was, of course, a burlesque, and we hope that any listeners who did not realize it will accept our sincere apologies for any uneasiness caused.

London is safe. Big Ben is still chiming, and all is well.

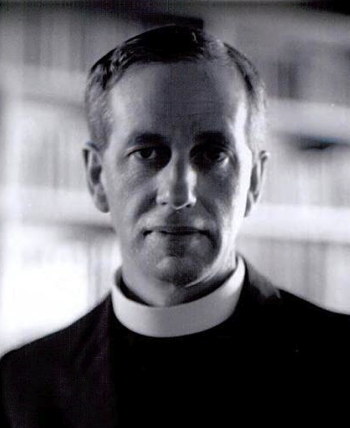

Father Ronald Knox

Part of the reason why so many people mistook the broadcast for actual news was the political context of the times. The Russian Revolution of 1917 was still a relatively recent event, fresh in people's minds. So when listeners heard the report of workers running amok in London, it seemed believable that what had happened in Russia might now be happening in the United Kingdom, especially if they had missed the beginning of the broadcast.

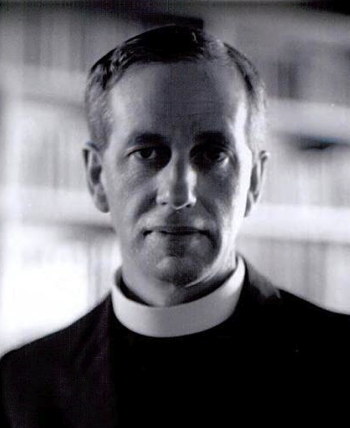

Civil unrest was a real possibility at the time of Father Knox's broadcast.

Here police charge at striking workers in South London, May 1926.

Of course, most people did realize it was a burlesque and were able to enjoy the comically incongruous parts of the broadcast, such as the detail about the leader of the mob, Mr. Popplebury, who was also "secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theater Queues."

Nevertheless, the broadcast caused widespread confusion and concern throughout Great Britian. The telephone exchange at the Savoy reported receiving over 200 inquiries, some from as far away as Manchester and New Castle, asking if the hotel was in ruins, and in some small towns the police reported that they were still receiving anxious calls about the fate of London the next morning.

Links and References

"England fooled by radio burlesque." (Apr 25, 1926).

The Sioux City Sunday Journal.

Comments