James Graham was one of the most notorious quacks of the 18th century. He was also extremely popular, attracting scores of followers who swore by the efficacy of his 'electric medicine.'

Graham was born in England in 1745, the son of a saddler. He studied medicine at Edinburgh, and though he never completed his studies there, he called himself a doctor anyway.

'Dr. Graham' moved to America while he was in his 20s. He travelled around for a while before settling in Philadelphia where he advertised himself as an eye specialist. While in Philadelphia, he became acquainted with Benjamin Franklin's electrical experiments, and he grew convinced that electricity was the cure for all ills.

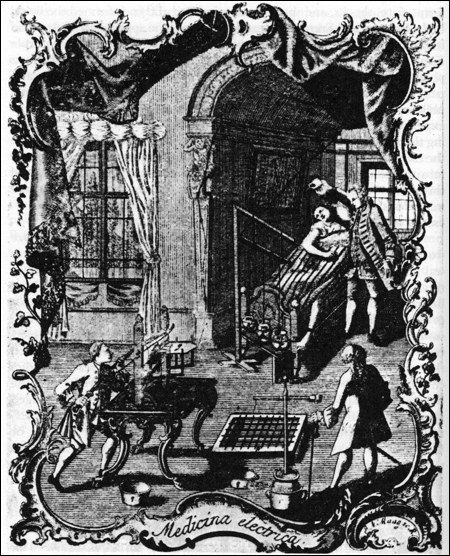

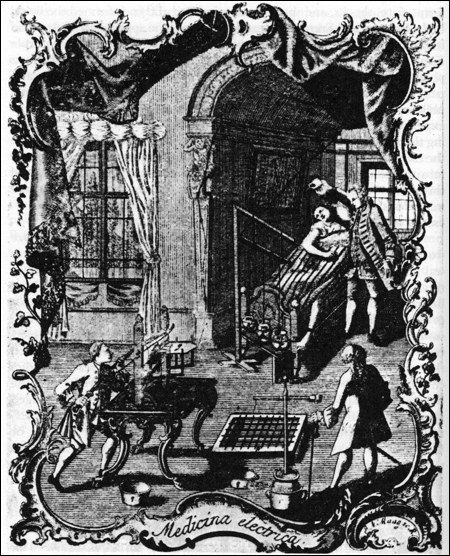

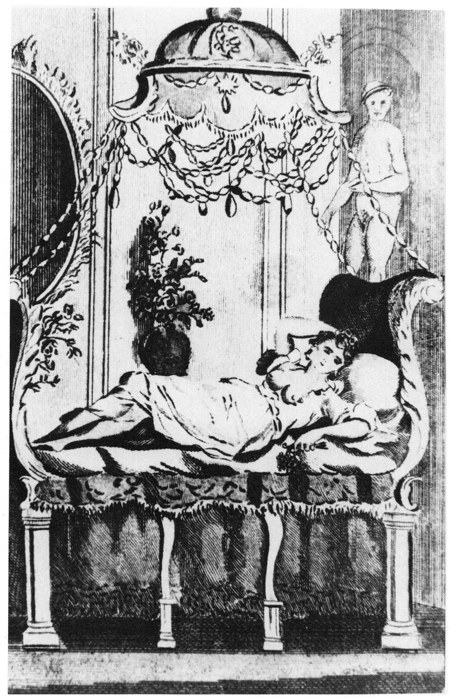

A practitioner of Electric Medicine at work.

From Johann Gottlieb Schaeffer,

Die electrische Medicin (Regensburg, 1766).

The Temple of Health

In 1775 Graham moved back to London where he began practicing his 'electric medicine' and attracting a rich and famous clientele. His therapy consisted of delivering a jolt of electricity to patients through a variety of electrical crowns and thrones.

Emboldened by his success, Graham began converting a large house in an opulent section of London into a magnificent Temple of Health. The doors of this temple opened in August, 1779, and patients began pouring in.

A variety of delights awaited those willing to pay the two-guinea fee to enter the Temple of Health. They could wander through ornately furnished rooms, breathe in the perfumed air, listen to music or hear Graham delivering lectures on health, buy medicines, inspect the 'medico-electrical apparatus,' or watch scantily-clad young women pose among the statues. One of the young women Graham employed was

Emma Lyon, who in later years would marry Sir William Hamilton and become Lord Horatio Nelson's lover.

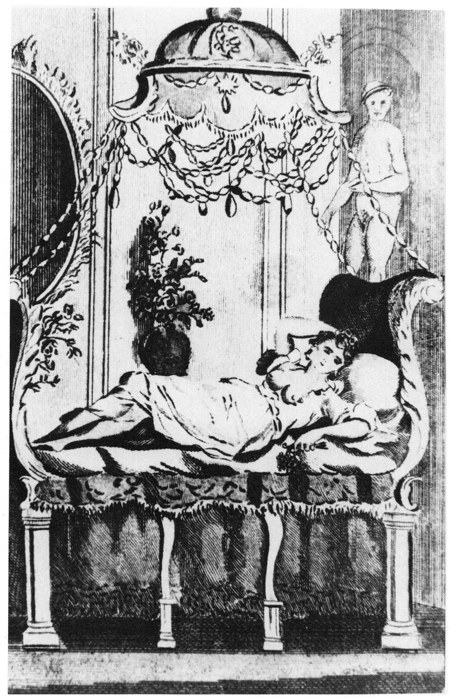

Emma Lyon, as she might have posed for patrons of Graham's Temple of Health

The Celestial Bed

The centerpiece of the Temple of Health was the 'Celestial Bed,' which was reserved for those able to afford the fee of £50 a night. Graham advertised that anyone who rented the bed for the night would be "blessed with progeny." Sterility or impotence would be cured.

The bed was twelve feet long by nine wide and could be tilted so that it lay at various angles. The mattress was filled with "sweet new wheat or oat straw, mingled with balm, rose leaves, and lavender flowers," as well as hair from the tails of fine English stallions.

As lovers lay in the bed, listening to the soft music playing and breathing in the fragrant air, they could stare up into the large mirror suspended above them on the ceiling. Behind them, electricity crackled across the headboard of the bed, filling the air with a magnetic fluid "calculated to give the necessary degree of strength and exertion to the nerves." The phrase "Be fruitful. Multiply and Replenish the Earth" was inscribed on the headboard.

A depiction of Graham's Celestial Bed

Oh, Wonderful Love

Despite the success of the Temple of Health, Graham was knee-deep in debt by 1784 and had to move to Edinburgh. Here he had a new revelation. Renouncing his old electrical theories, he took up the cause of mud baths, claiming that they were the secret to immortality. He argued that people could absorb all the nutrients necessary to sustain life simply by bathing in mud. He swore that he himself had survived two weeks immersed in mud with no nourishment except for a few drops of water.

Graham eventually was gripped by religious fervor and founded what he called the New Jerusalem Church (he was the only member). He began signing all his letters "Servant of the Lord, O.W.L." (Oh, Wonderful Love), and would engage in bizarre behavior such as stripping off all his clothes as he walked down the street in order to give it to the poor. He was arrested for this kind of behavior in 1794 and died soon after.

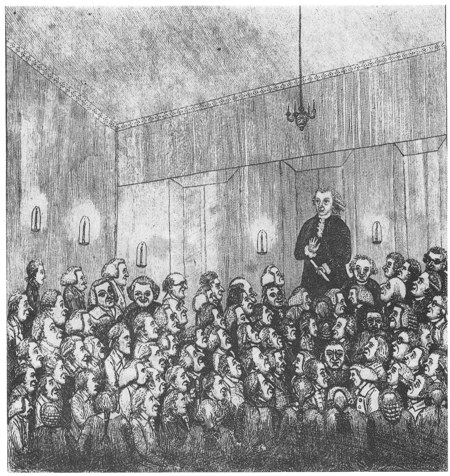

James Graham lecturing in Edinburgh, circa 1783

Links and References

- Bettany, George Thomas. "James Graham." in Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1921-1922, Vol.8: 323-26.

- The Temple of Health. Online article at Prints George.

- Newnham, Richard. The Guinness Book of Fakes, Frauds, & Forgeries. Guinness Publishing. 1991. 61-64.

Comments