The Official April Fool's Day FAQ

- What’s the origin of April Fool’s Day?

- What’s the earliest reference to April Fool’s Day?

- What are the rules and customs of April Fool’s Day?

- How is April Fool’s Day celebrated in different countries?

- What’s the correct spelling of April Fool’s Day?

- What are the best books and articles about April Fool’s Day?

I delve into the mystery of the origin of April Fool's Day in greater detail elsewhere, so I'll provide the condensed version here.

The folklorist Alan Dundes once noted, while discussing April Fool's Day, that "ultimate origins are almost always impossible to ascertain definitively." To this, another folklorist, Jack Santino, later added, "Explanations for the origins of April Fool's Day are many, and often as foolish as the day itself."

So if we keep in mind that we're never going to be able to pinpoint a precise moment in time when the custom of making April fools began, nor an exact reason why, and that most of the origin theories in circulation are somewhat far-fetched (to be charitable), then there are really only two things we can say with any certainty about the origin of the day:

In the ancient world, we find a number of spring festivals, many of which continue to be celebrated to this day. The ancient Romans observed Hilaria the day after the vernal equinox by allowing people to dress up in disguise as anyone they wished. And on the Veneralia, on April 1 itself, Roman women honored the fertility goddess Fortuna Virilis by entering the men's bathing complexes naked and burning incense, praying that the deity would help conceal their physical imperfections from male eyes. In India, there was the spring festival of Holi, which dates back to the 3rd century (and remains an active holiday). It involved people partying in the streets, throwing colored powder and water at each other, and, according to some 19th century sources, playing pranks such as sending victims on fools' errands. The Persians had Sizdah Bedar, dating back to the 6th century BC (and still being celebrated). It was held on April 1. People headed outdoors, had picnics, participated in games and sports, and played jokes on each other. Finally, the ancient Jewish festival of Purim (at the start of Spring) was a time of satire and frivolity, when people dressed up in costumes and performed "Purim spiels," comic plays designed to evoke laughter. Again, it's very much still in existence.

Girls spraying each other with colored water at Holi, circa 1640

There's no evidence that April Fool's Day descended directly from any of these festivals. Instead, it's more likely that April Fool's Day resembles these other celebrations because they're all manifestations of a deeper pattern of folk behavior — an instinct to respond to the arrival of spring with festive mischief and symbolic misrule.

In fact, by the late Middle Ages, April Fool's Day was only one of a number of spring festivals that had emerged in Europe. Preceding Lent, there were Shrovetide celebrations in the north, and the Carnival tradition in Latin Europe. In Portugal, there was a custom of throwing water and flour on people on the Sunday and Monday prior to Lent. May Day (May 1) was a day for playing pranks in many countries (particularly England, Denmark, and Sweden). Both Śmigus-Dyngus Day (on Easter Monday) in Poland, and Royal Oak Day, aka Shig-Shag Day (May 29) in England involved elements of ritual mischief. And, of course, there was Easter itself which, though more subdued, was nevertheless a time for games and merrymaking.

Shrove Tuesday celebration, as depicted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1559

Anthropologists can only speculate about why, but one possibility is that the misbehavior and playful frolic mimics the creative fertile energies that are returning to the world after winter. And allowing this frolic for only a brief period of time is a symbolic way of trying to harness and control this creative force, lest it grow out of control.

Another theory is that the pranks associated with these festivals act as a kind of calendrical hazing ritual. Pranks and hazing rituals are common rites of passage during major life changes such as getting married (think of tin cans on the back of the car), starting a new job, starting school, or birthdays (birthday spanking). So the theory is that major changes during the year, such as the arrival of spring, similarly prompt people to respond with hazing rituals. And in line with this theory, it's worth noting that it's traditional to play pranks not only at the start of spring, but also at the start of winter (on Halloween), and in some cultures at the start of the new year as well. For instance, Spanish-speaking countries celebrate the Day of the Holy Innocents (a custom that is very similar to April Fool's Day, involving pranks and telling tall tales) at the end of the year, on December 28.

Hazing rituals are common during transitional events, such as getting married, starting school,

or starting a new cycle of seasons

For instance, a very popular theory (repeated year after year by the media) links the date to the French calendar reform of 1564. The story goes that in 1564, King Charles IX of France passed the Edict of Roussillon, decreeing that henceforth the year would begin on January 1, instead of April 1. But some people failed to hear about the change and continued to celebrate the new year on April 1. Therefore, people played pranks on them, making them the first April fools.

King Charles IX, who was only 14 years old when he passed the Edict of Roussillon

There's a number of things wrong with this theory. Most significantly, we know from textual references that the custom of April Fool's Day had already been well established by the 1560s. So the calendar reform cannot have been responsible for a custom that already existed beforehand. But also, April 1 was not considered the start of the year in any part of France before 1564. The year began on different days in different parts of the country (March 25, March 1, Easter, or January 1). One of the reasons for the reform was to impose a single calendrical system throughout the entire country.

The actual reason why April 1 is the day of the celebration is likely much simpler. During the middle ages, April was widely considered to be the first month of spring. Therefore, it was logical to observe a rite of spring on the first day of the first month of the season.

The folklorist Alan Dundes once noted, while discussing April Fool's Day, that "ultimate origins are almost always impossible to ascertain definitively." To this, another folklorist, Jack Santino, later added, "Explanations for the origins of April Fool's Day are many, and often as foolish as the day itself."

So if we keep in mind that we're never going to be able to pinpoint a precise moment in time when the custom of making April fools began, nor an exact reason why, and that most of the origin theories in circulation are somewhat far-fetched (to be charitable), then there are really only two things we can say with any certainty about the origin of the day:

- that the celebration is most likely a rite of spring;

- and that it was well established by the middle of the 16th century.

Rites of Spring

Rites of spring can be found in most cultures, and they usually follow a similar pattern. They're festive occasions when, for a brief period of time, social rules can be flouted and a certain amount of misbehavior, mischief, and deception is allowed.In the ancient world, we find a number of spring festivals, many of which continue to be celebrated to this day. The ancient Romans observed Hilaria the day after the vernal equinox by allowing people to dress up in disguise as anyone they wished. And on the Veneralia, on April 1 itself, Roman women honored the fertility goddess Fortuna Virilis by entering the men's bathing complexes naked and burning incense, praying that the deity would help conceal their physical imperfections from male eyes. In India, there was the spring festival of Holi, which dates back to the 3rd century (and remains an active holiday). It involved people partying in the streets, throwing colored powder and water at each other, and, according to some 19th century sources, playing pranks such as sending victims on fools' errands. The Persians had Sizdah Bedar, dating back to the 6th century BC (and still being celebrated). It was held on April 1. People headed outdoors, had picnics, participated in games and sports, and played jokes on each other. Finally, the ancient Jewish festival of Purim (at the start of Spring) was a time of satire and frivolity, when people dressed up in costumes and performed "Purim spiels," comic plays designed to evoke laughter. Again, it's very much still in existence.

Girls spraying each other with colored water at Holi, circa 1640

There's no evidence that April Fool's Day descended directly from any of these festivals. Instead, it's more likely that April Fool's Day resembles these other celebrations because they're all manifestations of a deeper pattern of folk behavior — an instinct to respond to the arrival of spring with festive mischief and symbolic misrule.

In fact, by the late Middle Ages, April Fool's Day was only one of a number of spring festivals that had emerged in Europe. Preceding Lent, there were Shrovetide celebrations in the north, and the Carnival tradition in Latin Europe. In Portugal, there was a custom of throwing water and flour on people on the Sunday and Monday prior to Lent. May Day (May 1) was a day for playing pranks in many countries (particularly England, Denmark, and Sweden). Both Śmigus-Dyngus Day (on Easter Monday) in Poland, and Royal Oak Day, aka Shig-Shag Day (May 29) in England involved elements of ritual mischief. And, of course, there was Easter itself which, though more subdued, was nevertheless a time for games and merrymaking.

Shrove Tuesday celebration, as depicted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1559

Pranks and Springtime

Why do people in so many cultures respond to the arrival of spring with pranks and mischief? Anthropologists can only speculate about why, but one possibility is that the misbehavior and playful frolic mimics the creative fertile energies that are returning to the world after winter. And allowing this frolic for only a brief period of time is a symbolic way of trying to harness and control this creative force, lest it grow out of control.

Another theory is that the pranks associated with these festivals act as a kind of calendrical hazing ritual. Pranks and hazing rituals are common rites of passage during major life changes such as getting married (think of tin cans on the back of the car), starting a new job, starting school, or birthdays (birthday spanking). So the theory is that major changes during the year, such as the arrival of spring, similarly prompt people to respond with hazing rituals. And in line with this theory, it's worth noting that it's traditional to play pranks not only at the start of spring, but also at the start of winter (on Halloween), and in some cultures at the start of the new year as well. For instance, Spanish-speaking countries celebrate the Day of the Holy Innocents (a custom that is very similar to April Fool's Day, involving pranks and telling tall tales) at the end of the year, on December 28.

Hazing rituals are common during transitional events, such as getting married, starting school,

or starting a new cycle of seasons

Why April 1?

So April Fool's Day is most likely a rite of spring. But why is it observed on April 1 specifically? Why not on another day in the spring, such April 2, or March 28? This is the question that's inspired a lot of the most farfetched theories.For instance, a very popular theory (repeated year after year by the media) links the date to the French calendar reform of 1564. The story goes that in 1564, King Charles IX of France passed the Edict of Roussillon, decreeing that henceforth the year would begin on January 1, instead of April 1. But some people failed to hear about the change and continued to celebrate the new year on April 1. Therefore, people played pranks on them, making them the first April fools.

King Charles IX, who was only 14 years old when he passed the Edict of Roussillon

There's a number of things wrong with this theory. Most significantly, we know from textual references that the custom of April Fool's Day had already been well established by the 1560s. So the calendar reform cannot have been responsible for a custom that already existed beforehand. But also, April 1 was not considered the start of the year in any part of France before 1564. The year began on different days in different parts of the country (March 25, March 1, Easter, or January 1). One of the reasons for the reform was to impose a single calendrical system throughout the entire country.

The actual reason why April 1 is the day of the celebration is likely much simpler. During the middle ages, April was widely considered to be the first month of spring. Therefore, it was logical to observe a rite of spring on the first day of the first month of the season.

This is another way of asking, how long have people been celebrating April Fool's Day?

The earliest unambiguous reference that is currently known is found in a poem by the Flemish writer Eduard De Dene, published in 1561 (more details below). So we can say that April Fool's Day has existed since at least the mid-sixteenth centuy.

However, some other possible earlier references have been suggested. These earlier possibilities are problematic, but let's review them.

Geoffrey Chaucer

The claim derives from a line in the Nun's Priest's Tale which describes the tale as taking place "Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two" (i.e. 32 days since March began). This would place it on either April 1 or 2.

Coupled with the fact that the tale involves trickery (a fox fooling a rooster, and then getting fooled back), this suggests that Chaucer (so the argument goes) purposefully set the tale on April 1 as an allusion to April Fool's Day.

The argument seems sound, until one considers that four lines later Chaucer goes on to tell us that the tale takes place when the sun "in the signe of Taurus had y-runne / Twenty degrees and one, and somewhat more."

If the sun is in the sign of Taurus (which it is from April 20 to May 21), as Chaucer specifically says it is, how could the tale possibly be set on April 1? The two dates contradict each other.

Many Chaucer scholars resolve this contradiction by arguing that the phrase "syn March bigan" may have been a typo by a medieval scribe, and that Chaucer intended to write "syn March was gone," since if we count 32 days from the end of March, we arrive at May 2 or 3, in the sign of Taurus.

But let's assume that Chaucer did set the Nun's Priest's Tale on April 1, and that he intended this to be a reference to April Fool's Day. We then would have to explain why there's a complete absence of references to the custom of April foolery in the English literature of the 15th and 16th centuries. There's nothing in the plays of the period — no mention of the day in Shakespeare. Nor is it ever referred to in diaries or letters.

It's not until the late 17th century that we find the first unambiguous English-language references to April Fool's Day. Francis Osborne, in his Deductions from the History of the Earl of Essex (published in 1659), mentions the "impertinent errands, as the Dutch youth do [put upon] fools on the second of April." And John Aubrey, in his Remains of Gentilism and Judaism (published in 1686), notes the existence of "Fooles holy day. We observe it on ye first of April. And so it is kept in Germany everywhere."

Both these writers associated the tradition of April Fool's Day with foreign countries (Netherlands and Germany). And Osborne didn't seem very familiar with the custom, given that he thought it was celebrated on the second of April, not the first.

So if English writers of the late seventeenth century believed that April Fool's Day was a foreign custom, it's difficult to understand why Chaucer, writing almost 300 years before, would have known about it. And even if he did somehow know about it, why would he have assumed that his English readers also were familiar with it.

In fact, the evidence suggests that Chaucer had no knowledge of April Fool's Day and therefore couldn't have intended to allude to it. Nor, in all likelihood, did he even intend to set the Nun's Priest's Tale on April 1.

Note: I examine the Chaucer/April Fool controversy in more detail elsewhere.

The term appears in several late-medieval French poems — first in the work of Pierre Michault (1466) and next in La Livre de la Deablerie (1508), by Eloy d'Amerval. This has led some to suggest, quite reasonably, that these may be early April Fool's Day references.

However, etymologists believe that the phrase 'poisson d'Avril' originally referred to a matchmaker, or to someone who delivered messages between two lovers. It was only in the late 17th century that the phrase acquired its modern association with April Fool's Day.

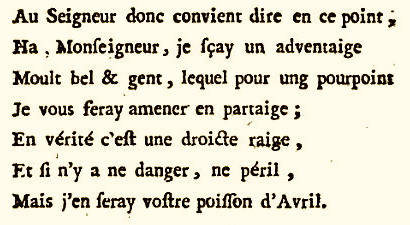

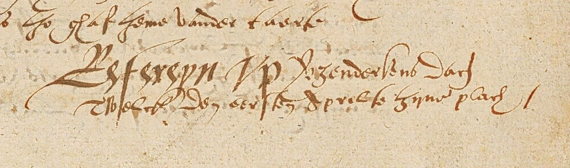

And if we examine these late-medieval poems, we see that this is the case. For example, Michault's poem describes the advice being given to a page, who is being told how to deliver messages between a lord and lady to further their illicit affair, and how to do this to his own advantage. Michault writes:

There's no indication that this has anything to do with April Fool's Day.

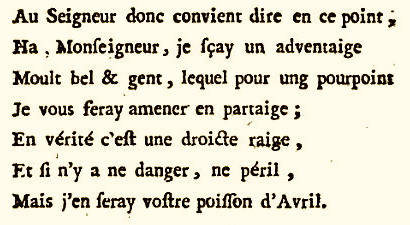

Likewise, d'Amerval wrote, "le chief des ruffyens, Houlier, putier, macquereau infame De maint homme et de mainte fame, Poisson d'Apvril." Loosely translated, this means something like, "chief ruffian, whore-monger, pimp of many a man and many a woman, panderer (April fish)." The way d'Amerval is using the phrase doesn't suggest any connection with April Fool's Day.

Therefore, these early uses of the phrase 'poisson d'Avril,' although intriguing, do not appear to be references to April Fool's Day.

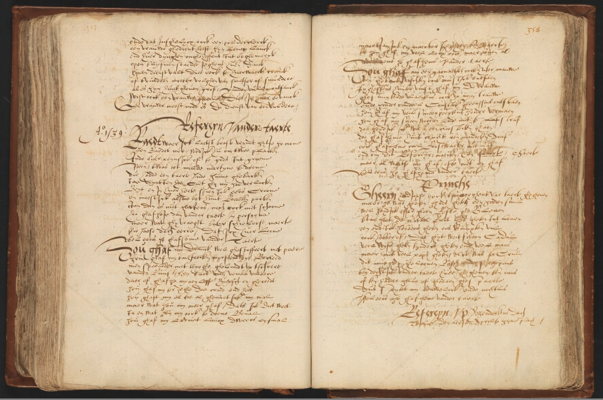

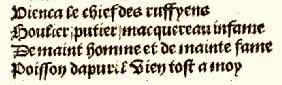

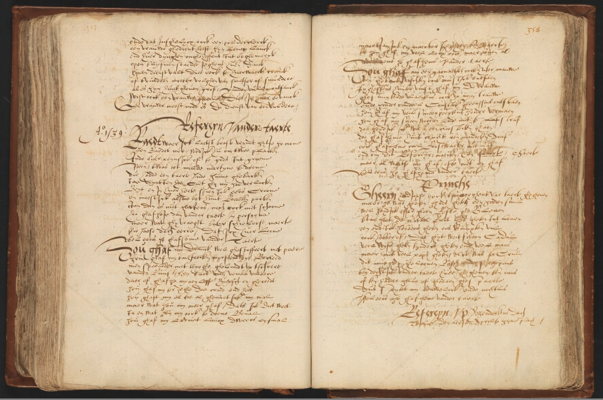

De Dene's Testament Rhetoricael, page 358.

The 'April Fool' poem begins on the bottom of the right-hand page. (Detail below)

There's no doubt that the poem is about April Fool's Day. In fact, in Belgium April 1 is still referred to as "Verzenderkensdag".

So this poem is the earliest unambiguous reference to April Fool's Day that we currently know of. Its existence establishes that the Dutch have been playing pranks on April 1 since at least the mid-sixteenth century.

Given that De Dene assumes his readers are familiar with "verzendekens dach," it's probable that the custom is much older than the 1560s. But exactly how much older, we don't know.

The earliest unambiguous reference that is currently known is found in a poem by the Flemish writer Eduard De Dene, published in 1561 (more details below). So we can say that April Fool's Day has existed since at least the mid-sixteenth centuy.

However, some other possible earlier references have been suggested. These earlier possibilities are problematic, but let's review them.

Chaucer

Within the past decade, an argument has gained popularity online claiming that Chaucer alluded to April Fool's Day in The Canterbury Tales, completed circa 1392. If true, it would be the first time the celebration was mentioned in any language. In fact, it would predate any other reference by a good margin.

Geoffrey Chaucer

The claim derives from a line in the Nun's Priest's Tale which describes the tale as taking place "Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two" (i.e. 32 days since March began). This would place it on either April 1 or 2.

Coupled with the fact that the tale involves trickery (a fox fooling a rooster, and then getting fooled back), this suggests that Chaucer (so the argument goes) purposefully set the tale on April 1 as an allusion to April Fool's Day.

The argument seems sound, until one considers that four lines later Chaucer goes on to tell us that the tale takes place when the sun "in the signe of Taurus had y-runne / Twenty degrees and one, and somewhat more."

If the sun is in the sign of Taurus (which it is from April 20 to May 21), as Chaucer specifically says it is, how could the tale possibly be set on April 1? The two dates contradict each other.

Many Chaucer scholars resolve this contradiction by arguing that the phrase "syn March bigan" may have been a typo by a medieval scribe, and that Chaucer intended to write "syn March was gone," since if we count 32 days from the end of March, we arrive at May 2 or 3, in the sign of Taurus.

But let's assume that Chaucer did set the Nun's Priest's Tale on April 1, and that he intended this to be a reference to April Fool's Day. We then would have to explain why there's a complete absence of references to the custom of April foolery in the English literature of the 15th and 16th centuries. There's nothing in the plays of the period — no mention of the day in Shakespeare. Nor is it ever referred to in diaries or letters.

It's not until the late 17th century that we find the first unambiguous English-language references to April Fool's Day. Francis Osborne, in his Deductions from the History of the Earl of Essex (published in 1659), mentions the "impertinent errands, as the Dutch youth do [put upon] fools on the second of April." And John Aubrey, in his Remains of Gentilism and Judaism (published in 1686), notes the existence of "Fooles holy day. We observe it on ye first of April. And so it is kept in Germany everywhere."

Both these writers associated the tradition of April Fool's Day with foreign countries (Netherlands and Germany). And Osborne didn't seem very familiar with the custom, given that he thought it was celebrated on the second of April, not the first.

So if English writers of the late seventeenth century believed that April Fool's Day was a foreign custom, it's difficult to understand why Chaucer, writing almost 300 years before, would have known about it. And even if he did somehow know about it, why would he have assumed that his English readers also were familiar with it.

In fact, the evidence suggests that Chaucer had no knowledge of April Fool's Day and therefore couldn't have intended to allude to it. Nor, in all likelihood, did he even intend to set the Nun's Priest's Tale on April 1.

Note: I examine the Chaucer/April Fool controversy in more detail elsewhere.

Poisson d'Avril

The French term for 'April Fool' is 'poisson d'Avril.' It translates literally as 'April Fish.' The term appears in several late-medieval French poems — first in the work of Pierre Michault (1466) and next in La Livre de la Deablerie (1508), by Eloy d'Amerval. This has led some to suggest, quite reasonably, that these may be early April Fool's Day references.

However, etymologists believe that the phrase 'poisson d'Avril' originally referred to a matchmaker, or to someone who delivered messages between two lovers. It was only in the late 17th century that the phrase acquired its modern association with April Fool's Day.

And if we examine these late-medieval poems, we see that this is the case. For example, Michault's poem describes the advice being given to a page, who is being told how to deliver messages between a lord and lady to further their illicit affair, and how to do this to his own advantage. Michault writes:

Now you should say to the Lord, ah, sir, I know of a fine and pleasing advantage, by which for a doublet I shall bring you together; truthfully, carnal love is a proper desire, and thus there is no danger or peril, but still, I shall be your 'poisson d'avril'.

There's no indication that this has anything to do with April Fool's Day.

Likewise, d'Amerval wrote, "le chief des ruffyens, Houlier, putier, macquereau infame De maint homme et de mainte fame, Poisson d'Apvril." Loosely translated, this means something like, "chief ruffian, whore-monger, pimp of many a man and many a woman, panderer (April fish)." The way d'Amerval is using the phrase doesn't suggest any connection with April Fool's Day.

Therefore, these early uses of the phrase 'poisson d'Avril,' although intriguing, do not appear to be references to April Fool's Day.

Verzenderkensdag

In 1561, the Flemish poet Eduard De Dene, who lived in the city of Bruges, published his Testament Rhetoricael. The book consisted of a large collection of poems and songs, and 'published' is perhaps not the right word to describe its debut, since it was entirely handwritten. But on page 358, the book included a poem titled "Refereyn vp verzendekens dach / Twelck den eersten April te zyne plach." This is late-medieval Dutch meaning (approximately) "Refrain on fool's errand-day / which is the first of April." The poem described a nobleman who sent his servant back and forth on various absurd errands on April 1st, ostensibly to help prepare for a wedding feast.

De Dene's Testament Rhetoricael, page 358.

The 'April Fool' poem begins on the bottom of the right-hand page. (Detail below)

There's no doubt that the poem is about April Fool's Day. In fact, in Belgium April 1 is still referred to as "Verzenderkensdag".

So this poem is the earliest unambiguous reference to April Fool's Day that we currently know of. Its existence establishes that the Dutch have been playing pranks on April 1 since at least the mid-sixteenth century.

Given that De Dene assumes his readers are familiar with "verzendekens dach," it's probable that the custom is much older than the 1560s. But exactly how much older, we don't know.

April Fool's Day is a celebration of mischief and misbehavior, but it's not a complete free-for-all. There are rules about how it should be observed. Unwritten rules, but ones that nevertheless hold the weight of hundreds of years of tradition. And even for those who do not plan to play pranks, there are customs about what are appropriate activities to engage in on the day.

The essence of an April first prank is to fool a victim. Therefore, pranks that involve no deception are considered out of place. Traditional April fool pranks include gluing a coin to the pavement, putting salt in a sugar bowl, and tricking someone into believing their shoelaces are untied.

A typical April Fool's Day prank: gluing a coin to the sidewalk

and watching as people try to pick it up

On Halloween, by contrast, pranks often assume a darker, more malevolent quality and do not necessarily involve any deception. Traditional Halloween pranks include soaping windows, throwing eggs at cars, and covering houses with toilet paper.

It's considered acceptable for April Fool's Day pranks to cause some inconvience to their victims. Making people feel embarrassed or irritated is okay. Wasting people's time — okay. Making them do some work to undo the prank — also okay. After all, the entire point of April Fool's Day is to make people look foolish.

However, inconvenience should never turn into actual violence or harm. This includes causing serious psychological harm. No one should get hurt. Nor should property be permanently damaged. Nor can April 1 be used as an excuse to engage in any illegal activity.

The lore of April Fool's Day is full of examples of people who failed to understand these limits and got their comeuppance. For instance, 19th century newspapers frequently repeated the story of a Parisian woman who, on April 1, 1817, stole her friend's jeweled watch. When the gendarmes arrested her, she initially denied having taken the watch, but when it was later found in her apartment, she explained that the theft had merely been an April fool joke. The story concluded, "her ill-timed pleasantry was punished by the jocular sentence that she should be incarcerated until the first of April of the following year, 1818."

There's probably an element of ancient folk belief lurking behind the rule. April Fool's Day honors the spirit of Folly, which is a powerful force. And as such, it needs to be contained within strict temporal limits, lest it overspill its boundaries and cause chaos throughout the rest of the year.

Although there's no known record of this rule having been explicitly articulated outside of English-speaking countries, it's nevertheless widely observed, for a practical reason. People are more likely to be fooled in the morning, when they might not remember what day it is. As the day progresses, they'll wise up, and pranks against them have a higher chance of failing.

The earliest reference to this rule is found in the British journal Notes and Queries (Aug 11, 1855) by a correspondent who noted that it was a tradition in the county of Hampshire that those who played pranks after twelve o'clock on April 1 would be greeted by the following verse:

Half-a-century later (Apr. 15, 1905), several more correspondents to Notes and Queries recalled the rule being strictly in force during their childhood in the mid-nineteenth century. For instance, Harry Hems. wrote: "It is fully half a century ago since I left school, but it is well within my recollection that the practice of playing pranks upon one's fellow pupils on 1 April was not permissible after noontide. Then those who had been tricked by their companions were pointed at by the latter, and the following somewhat dense couplet hurled at them: 'April's gone, and May's come; You're a fool and I'm none!'"

Thos. Ratcliffe remembered that pranks perpetrated after noon were greeted by a slightly different response: "April Fool Day past an' gone, You're ten fools for makin' me one!"

In a 1959 study of British schoolchildren, Peter and Iona Opie found that the rule was still enforced every April 1 in school yards. Several decades later, child psychologist Brian Sutton-Smith also observed the rule in effect in New Zealand schools.

During the past three decades, it's become common for companies to issue spoof announcements on the morning of the first, and wait unil noon to reveal the joke, thereby staying true to the rule. The restaurant chain Taco Bell did this in 1996 when it ran full-page ads in American papers announcing that they were purchasing the Liberty Bell and renaming it the Taco Liberty Bell. The company then issued a press release at noon confessing to the hoax.

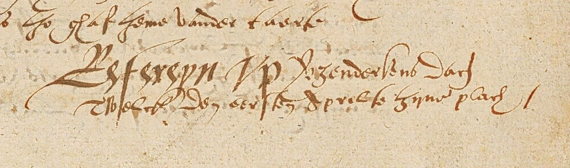

Another strategy used by advertisers is to send a spoof press release to reporters a few days early, with instructions that the announcement should be "embargoed" until April 1. (That is, it should not be reported as news until then.) This ensures that the spoof will appear in papers on the morning of the first. However, reporters do not always obey the embargo. A famous example of this occurred in 1998 when Guinness issued a press release on March 30 (embargoed until April 1) announcing that, in honor of the upcoming millennium celebration, they had reached a deal with the Greenwich Observatory such that Greenwich Mean Time would temporarily be renamed Guinness Mean Time. The Financial Times broke the embargo a day early, not realizing the announcement was a joke, and criticized the supposed corporate sponsorship as setting a "brash tone for the millennium".

The Financial Times mistakenly reported Guinness's spoof a day early

The global reach of the internet has provided a new incentive to make spoof announcements as early as possible (thus staying true to the 'before noon' rule, even if unwittingly), because if the joke is released too late, it may unfairly confuse people in time zones where it's no longer April 1. This happened on April 1, 2013 when the actress Lindsay Lohan waited until 10:35 pm (pacific time zone) to tweet that she was pregnant, which she intended as a joke. But her attempt at humor was widely criticized because many of her followers were on the east coast, or in Europe, where it was already April 2. Therefore, they assumed the news was real.

April 1 was long believed to be a bad day to schedule important events. It was said that those who wed on April 1 would never be able to trust their spouse, dooming their marriage to failure. Or that a man who married on April 1 would always play second fiddle to his wife. After Napoleon wed Marie-Louise of Austria on April 1, 1810, his subjects mockingly began to call him a "poisson d'Avril" (April fish). The mockery was even put to rhyme: "Napoleon, Napoleon, / We thought you were a nice Italian dish! / Instead we have discovered that you are a small April fish!"

In rural communities, it was considered unwise to sow any crops on April 1, because these crops would fail. Children born on April 1 were thought to be unlucky children who would grow up unruly, out of control. And the sinking of the R.M.S. Titanic has been attributed to the fact that it completed its sea trials on April 1, 1912. (Although the trials were actually delayed until April 2 due to strong winds.)

Along similar lines, it was said that if someone discovered they had been made an April fool and lost their temper, that would cause them bad luck in the future. However, a rare positive superstition predicted that if a bachelor was fooled by a pretty girl on April 1 (and, one assumes, didn't lose his temper) that meant he would marry her.

Such superstitious beliefs are no longer given much credence. Nevertheless, it remains common to avoid scheduling important events on April 1. This is particularly true in both government and business. The practical reason given for this avoidance is that people may think that any kind of major announcement or product launch on April 1 is a joke. For instance, in 2012, when New Zealand had scheduled new traffic regulations to start on April 1, the Transport Minister changed the date at the last minute to March 25, citing concerns that people would not take the new rules seriously.

However, remnants of the old superstitious beliefs may still lurk behind some decisions to avoid April 1. In 2012, when Chrysler pushed back the production launch of the Dodge Dart until after April 1, the reason they gave was that they wanted to "avoid being jinxed" by an April Fool's Day Launch.

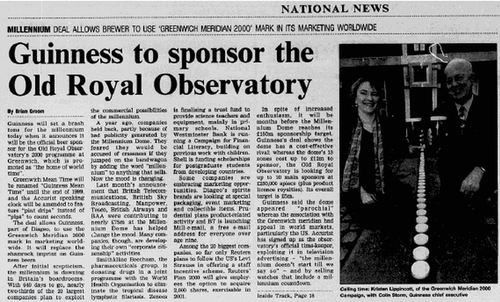

Of course, sometimes companies will purposefully launch products on April 1 to defy convention. The most famous example of this occurred on April 1, 2004 when Google debuted its new Gmail email service, that came with a gigabyte of free storage. At the time, it was unheard of to offer so much free storage, so there was widespread speculation that the announcement was a hoax. This speculation was fueled by the fact that Google had already established a tradition of making spoof announcements on April 1.

Another famous April Fool's Day launch occurred on April 1, 1976 when Apple Computer was founded by Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne. According to histories of the company, this date was chosen purposefully as a way of saying "we want to be different".

Apple Computer: founded on April Fool's Day, 1976

Do No Harm (and nothing illegal)

The first of April is a time for lighthearted humor, and pranks perpetrated on the day should reflect this. Ideally an April Fool's Day prank should be funny to everyone involved when it's all over. At least, that's the goal. The essence of an April first prank is to fool a victim. Therefore, pranks that involve no deception are considered out of place. Traditional April fool pranks include gluing a coin to the pavement, putting salt in a sugar bowl, and tricking someone into believing their shoelaces are untied.

A typical April Fool's Day prank: gluing a coin to the sidewalk

and watching as people try to pick it up

On Halloween, by contrast, pranks often assume a darker, more malevolent quality and do not necessarily involve any deception. Traditional Halloween pranks include soaping windows, throwing eggs at cars, and covering houses with toilet paper.

It's considered acceptable for April Fool's Day pranks to cause some inconvience to their victims. Making people feel embarrassed or irritated is okay. Wasting people's time — okay. Making them do some work to undo the prank — also okay. After all, the entire point of April Fool's Day is to make people look foolish.

However, inconvenience should never turn into actual violence or harm. This includes causing serious psychological harm. No one should get hurt. Nor should property be permanently damaged. Nor can April 1 be used as an excuse to engage in any illegal activity.

The lore of April Fool's Day is full of examples of people who failed to understand these limits and got their comeuppance. For instance, 19th century newspapers frequently repeated the story of a Parisian woman who, on April 1, 1817, stole her friend's jeweled watch. When the gendarmes arrested her, she initially denied having taken the watch, but when it was later found in her apartment, she explained that the theft had merely been an April fool joke. The story concluded, "her ill-timed pleasantry was punished by the jocular sentence that she should be incarcerated until the first of April of the following year, 1818."

No Pranks After Noon

This rule appears to be peculiar to English-speaking countries. The custom is that pranks can only be perpetrated until twelve o'clock noon. After that time, anyone who tries to play a prank is himself (or herself) the fool.There's probably an element of ancient folk belief lurking behind the rule. April Fool's Day honors the spirit of Folly, which is a powerful force. And as such, it needs to be contained within strict temporal limits, lest it overspill its boundaries and cause chaos throughout the rest of the year.

Although there's no known record of this rule having been explicitly articulated outside of English-speaking countries, it's nevertheless widely observed, for a practical reason. People are more likely to be fooled in the morning, when they might not remember what day it is. As the day progresses, they'll wise up, and pranks against them have a higher chance of failing.

The earliest reference to this rule is found in the British journal Notes and Queries (Aug 11, 1855) by a correspondent who noted that it was a tradition in the county of Hampshire that those who played pranks after twelve o'clock on April 1 would be greeted by the following verse:

| April fool's gone past, You're the biggest fool at last; When April fool comes again, You'll be the biggest fool then. |

Half-a-century later (Apr. 15, 1905), several more correspondents to Notes and Queries recalled the rule being strictly in force during their childhood in the mid-nineteenth century. For instance, Harry Hems. wrote: "It is fully half a century ago since I left school, but it is well within my recollection that the practice of playing pranks upon one's fellow pupils on 1 April was not permissible after noontide. Then those who had been tricked by their companions were pointed at by the latter, and the following somewhat dense couplet hurled at them: 'April's gone, and May's come; You're a fool and I'm none!'"

Thos. Ratcliffe remembered that pranks perpetrated after noon were greeted by a slightly different response: "April Fool Day past an' gone, You're ten fools for makin' me one!"

In a 1959 study of British schoolchildren, Peter and Iona Opie found that the rule was still enforced every April 1 in school yards. Several decades later, child psychologist Brian Sutton-Smith also observed the rule in effect in New Zealand schools.

During the past three decades, it's become common for companies to issue spoof announcements on the morning of the first, and wait unil noon to reveal the joke, thereby staying true to the rule. The restaurant chain Taco Bell did this in 1996 when it ran full-page ads in American papers announcing that they were purchasing the Liberty Bell and renaming it the Taco Liberty Bell. The company then issued a press release at noon confessing to the hoax.

Another strategy used by advertisers is to send a spoof press release to reporters a few days early, with instructions that the announcement should be "embargoed" until April 1. (That is, it should not be reported as news until then.) This ensures that the spoof will appear in papers on the morning of the first. However, reporters do not always obey the embargo. A famous example of this occurred in 1998 when Guinness issued a press release on March 30 (embargoed until April 1) announcing that, in honor of the upcoming millennium celebration, they had reached a deal with the Greenwich Observatory such that Greenwich Mean Time would temporarily be renamed Guinness Mean Time. The Financial Times broke the embargo a day early, not realizing the announcement was a joke, and criticized the supposed corporate sponsorship as setting a "brash tone for the millennium".

The Financial Times mistakenly reported Guinness's spoof a day early

The global reach of the internet has provided a new incentive to make spoof announcements as early as possible (thus staying true to the 'before noon' rule, even if unwittingly), because if the joke is released too late, it may unfairly confuse people in time zones where it's no longer April 1. This happened on April 1, 2013 when the actress Lindsay Lohan waited until 10:35 pm (pacific time zone) to tweet that she was pregnant, which she intended as a joke. But her attempt at humor was widely criticized because many of her followers were on the east coast, or in Europe, where it was already April 2. Therefore, they assumed the news was real.

April 1 As An Unlucky Day

It's an old superstition that April 1 is a cursed, unlucky day. Various religious reasons are sometimes given for this. For instance, April 1 is said to be the birthday of Judas, or the day Judas hanged himself, or the day the devil was banished from Heaven.April 1 was long believed to be a bad day to schedule important events. It was said that those who wed on April 1 would never be able to trust their spouse, dooming their marriage to failure. Or that a man who married on April 1 would always play second fiddle to his wife. After Napoleon wed Marie-Louise of Austria on April 1, 1810, his subjects mockingly began to call him a "poisson d'Avril" (April fish). The mockery was even put to rhyme: "Napoleon, Napoleon, / We thought you were a nice Italian dish! / Instead we have discovered that you are a small April fish!"

In rural communities, it was considered unwise to sow any crops on April 1, because these crops would fail. Children born on April 1 were thought to be unlucky children who would grow up unruly, out of control. And the sinking of the R.M.S. Titanic has been attributed to the fact that it completed its sea trials on April 1, 1912. (Although the trials were actually delayed until April 2 due to strong winds.)

Along similar lines, it was said that if someone discovered they had been made an April fool and lost their temper, that would cause them bad luck in the future. However, a rare positive superstition predicted that if a bachelor was fooled by a pretty girl on April 1 (and, one assumes, didn't lose his temper) that meant he would marry her.

Such superstitious beliefs are no longer given much credence. Nevertheless, it remains common to avoid scheduling important events on April 1. This is particularly true in both government and business. The practical reason given for this avoidance is that people may think that any kind of major announcement or product launch on April 1 is a joke. For instance, in 2012, when New Zealand had scheduled new traffic regulations to start on April 1, the Transport Minister changed the date at the last minute to March 25, citing concerns that people would not take the new rules seriously.

However, remnants of the old superstitious beliefs may still lurk behind some decisions to avoid April 1. In 2012, when Chrysler pushed back the production launch of the Dodge Dart until after April 1, the reason they gave was that they wanted to "avoid being jinxed" by an April Fool's Day Launch.

Of course, sometimes companies will purposefully launch products on April 1 to defy convention. The most famous example of this occurred on April 1, 2004 when Google debuted its new Gmail email service, that came with a gigabyte of free storage. At the time, it was unheard of to offer so much free storage, so there was widespread speculation that the announcement was a hoax. This speculation was fueled by the fact that Google had already established a tradition of making spoof announcements on April 1.

Another famous April Fool's Day launch occurred on April 1, 1976 when Apple Computer was founded by Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne. According to histories of the company, this date was chosen purposefully as a way of saying "we want to be different".

Apple Computer: founded on April Fool's Day, 1976

April Fool's Day has become a global phenomenon, but there are regional variations in its customs and how it's celebrated.

In Flemish-speaking parts of Belgium and the Netherlands, April 1 is referred to as Verzenderkesdag (fool's errand day).

Likewise, in Scotland and parts of northern England, April 1 was traditionally known as Huntigowk Day, on account of the old custom of "hunting the gowk" on the first. A gowk was a cuckoo, but on April 1 it referred to the victim who was sent on a "gowk hunt". He was asked to deliver a note that, unbeknownst to him, read, "Never laugh, never smile, Hunt the gowk another milk" (or some variation of that). Recipients of this note would duly redirect its bearer elsewhere until the victim had been run all over town.

"Hunting the Gowk" - illustration by Freeman Martin (1975)

Icelanders had a custom of hlaupa april ("running April") very similar to the gowk hunt, but with the twist that the prank was only considered to have succeeded if the victim could be tricked into crossing three thresholds before realizing what was up.

Finally, one of the oldest German expressions for perpetrating an April fool joke, dating back to the early 1600s, is 'jemanden in den April schicken'. It translates literally as 'to send someone in April'. It appears to derive from the custom of sending people on foolish errands on April 1. (See What's the earliest German reference to April Fool's Day?).

In northern England and Scotland, there's also an old custom of playing pranks on the 2nd of April, but only a very specific type of prank — pinning paper tails on people's back. For which reason, April 2 was known as Taily Day (or, less often, Tail-pipe Day). In some areas, the ritual was to pin a note saying something such as "Kick Me" on a person's rear.

1931: Actresses demonstrate the 'Kick Me' prank

Theories about the origin of this phrase are almost as many (and as fanciful) as theories about the origin of April Fool's Day itself. For instance, one theory is that the phrase derives from the abundance of fish found in streams and rivers during early April, and the ease with which these fish can be caught with a hook and lure. Another theory is that the phrase is a corruption of the word 'passion,' from the passion plays performed during the middle ages that would depict how Christ was sent back and forth to torment him, from Annas to Caiaphas, on to Pilate, then Herod, and back to Pilate again. However, as noted above in What's the earliest reference to April Fool's Day, 'poisson d'Avril' only acquired its modern meaning of an April fool in the late 17th century. Before then, the phrase described someone who conveyed messages between two lovers.

Whatever the origin of the phrase might be, in France, french-speaking Belgium, and Italy, the fish is the primary symbol of April Fool's Day. In these areas, it used to be customary to send humorous postcards on April 1 with pictures of fish.

A poisson d'Avril postcard, circa 1905

By contrast, in all other areas, the fool or court jester is the primary symbol of the day. In some regions of England, an April Fool used to be called an "April Noddy" — noddy being an archaic term for a fool or simpleton.

German-speaking regions also had some variant terms for the April Fool, include April ochse (ox), April kalb (calf), April esel (ass), April gans (goose), and April affe (monkey). However, all those terms are somewhat archaic, and April narr (fool) is now the most popular symbol of April Fool's Day in Germany.

In countries where the fish is the symbol of April 1, it's long been traditional for children to celebrate the day by surreptitiously pinning paper fish on the backs of classmates or people in the street. In France and Belgium, many candy shops also sell chocolate fish on April 1.

A french boy pins a paper fish on the back of his brother - Apr 1, 1963

During the 19th century, newspapers only very occasionally ran fake stories on April 1. It was during the early 20th century, particularly with the increasing use of photographs in newspapers, that media hoaxes became a central part of the celebration.

Up until the 1930s, such hoaxes were known to be a specialty of the German media, by whom they were called Zeitungsente, or 'newspaper ducks'. However, newspapers throughout Europe and North America enthusiastically picked up the custom, and since the 1980s, it's been the British media that has been most closely associated with April first hoaxing. In America, many smaller, local papers have long traditions of April 1 hoaxes (or had, since many of these newspapers no longer exist), but the larger papers that aim for a national readership (such as the New York Times and Washington Post) generally do not participate in the custom (though there are a few rare exceptions).

A German April fool hoax from 1934, describing the supposed capture of the Loch Ness Monster.

It ran in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung

During the past four decades, news organizations in Asia, Africa, and South America began to adopt the custom of April 1 hoaxing from their counterparts in Europe and North America. In this way, the tradition of April Fool's Day has now spread throughout the entire world. However, people in Asia, Africa, and South America primarily know April 1 as a day for media hoaxes, and individuals in these regions do not, by and large, engage in pranks at home and the office in the way that (some) people in Europe and North America still do.

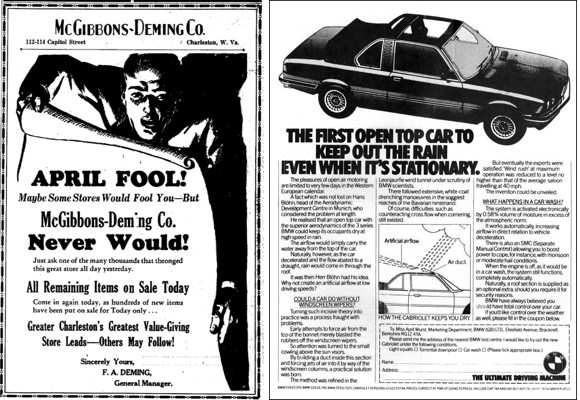

(left) A typical April fool ad from early in the 20th century, 1930;

(right) One of BMW's first April fool spoof ads. It ran in 1983.

During the 21st century, the Internet has massively accelerated the popularity of April 1 spoof advertising, because of the ease with which videos and photographs can be shared online. It has reached the point now where hundreds of companies (and even organizations such as the US Army) release spoof ads on April Fool's Day. Some advertisers note that they actually feel compelled to participate in the custom, lest people think their brand lacks a sense of humor.

And just like April fool media hoaxes before them, April fool spoof ads have become a global phenomenon.

A spoof ad for Domino's canned pizza that ran in Japan - Apr 1, 2013

April Fool's Day has also made fewer inroads into Spanish-speaking countries where the Day of the Holy Innocents is celebrated on Dec 28. This is a day for pranks and media hoaxes, very similar to April Fool's Day. But even in these countries, it is becoming more common for the media and advertisers to create hoaxes for April 1.

Fool's Errands

From the 16th to 18th centuries, the prank that was most closely associated with April 1 was the fool's errand — also known as a wild goose chase or (archaically) a 'sleeveless errand'. This emphasis still endures, at least linguistically, in certain areas. In Flemish-speaking parts of Belgium and the Netherlands, April 1 is referred to as Verzenderkesdag (fool's errand day).

Likewise, in Scotland and parts of northern England, April 1 was traditionally known as Huntigowk Day, on account of the old custom of "hunting the gowk" on the first. A gowk was a cuckoo, but on April 1 it referred to the victim who was sent on a "gowk hunt". He was asked to deliver a note that, unbeknownst to him, read, "Never laugh, never smile, Hunt the gowk another milk" (or some variation of that). Recipients of this note would duly redirect its bearer elsewhere until the victim had been run all over town.

"Hunting the Gowk" - illustration by Freeman Martin (1975)

Icelanders had a custom of hlaupa april ("running April") very similar to the gowk hunt, but with the twist that the prank was only considered to have succeeded if the victim could be tricked into crossing three thresholds before realizing what was up.

Finally, one of the oldest German expressions for perpetrating an April fool joke, dating back to the early 1600s, is 'jemanden in den April schicken'. It translates literally as 'to send someone in April'. It appears to derive from the custom of sending people on foolish errands on April 1. (See What's the earliest German reference to April Fool's Day?).

Time Limits

In England, and other English-speaking parts of the former British empire, it's considered a rule that pranks and hoaxes are only allowed on April 1 for a limited period of time: specifically, until noon (See Rules and Customs). After that, if someone tries to fool you, they become the fool and can be taunted with the rhyme: "April Fool's Day's past and gone, / You're the fool for making one." However, this rule only seems to hold true where English is spoken.In northern England and Scotland, there's also an old custom of playing pranks on the 2nd of April, but only a very specific type of prank — pinning paper tails on people's back. For which reason, April 2 was known as Taily Day (or, less often, Tail-pipe Day). In some areas, the ritual was to pin a note saying something such as "Kick Me" on a person's rear.

1931: Actresses demonstrate the 'Kick Me' prank

April Fish

In French and Italian an 'April Fool' is known as an 'April Fish' (French: poisson d'Avril; Italian: pesce d'Aprile). Theories about the origin of this phrase are almost as many (and as fanciful) as theories about the origin of April Fool's Day itself. For instance, one theory is that the phrase derives from the abundance of fish found in streams and rivers during early April, and the ease with which these fish can be caught with a hook and lure. Another theory is that the phrase is a corruption of the word 'passion,' from the passion plays performed during the middle ages that would depict how Christ was sent back and forth to torment him, from Annas to Caiaphas, on to Pilate, then Herod, and back to Pilate again. However, as noted above in What's the earliest reference to April Fool's Day, 'poisson d'Avril' only acquired its modern meaning of an April fool in the late 17th century. Before then, the phrase described someone who conveyed messages between two lovers.

Whatever the origin of the phrase might be, in France, french-speaking Belgium, and Italy, the fish is the primary symbol of April Fool's Day. In these areas, it used to be customary to send humorous postcards on April 1 with pictures of fish.

A poisson d'Avril postcard, circa 1905

By contrast, in all other areas, the fool or court jester is the primary symbol of the day. In some regions of England, an April Fool used to be called an "April Noddy" — noddy being an archaic term for a fool or simpleton.

German-speaking regions also had some variant terms for the April Fool, include April ochse (ox), April kalb (calf), April esel (ass), April gans (goose), and April affe (monkey). However, all those terms are somewhat archaic, and April narr (fool) is now the most popular symbol of April Fool's Day in Germany.

In countries where the fish is the symbol of April 1, it's long been traditional for children to celebrate the day by surreptitiously pinning paper fish on the backs of classmates or people in the street. In France and Belgium, many candy shops also sell chocolate fish on April 1.

A french boy pins a paper fish on the back of his brother - Apr 1, 1963

Worldwide Media Hoaxes

During the past 100 years, media hoaxes (humorous fake stories and photos created by news organizations) have become a central part of April Fool's Day. For many people, perhaps most, such hoaxes are the most highly anticipated feature of the day.During the 19th century, newspapers only very occasionally ran fake stories on April 1. It was during the early 20th century, particularly with the increasing use of photographs in newspapers, that media hoaxes became a central part of the celebration.

Up until the 1930s, such hoaxes were known to be a specialty of the German media, by whom they were called Zeitungsente, or 'newspaper ducks'. However, newspapers throughout Europe and North America enthusiastically picked up the custom, and since the 1980s, it's been the British media that has been most closely associated with April first hoaxing. In America, many smaller, local papers have long traditions of April 1 hoaxes (or had, since many of these newspapers no longer exist), but the larger papers that aim for a national readership (such as the New York Times and Washington Post) generally do not participate in the custom (though there are a few rare exceptions).

A German April fool hoax from 1934, describing the supposed capture of the Loch Ness Monster.

It ran in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung

During the past four decades, news organizations in Asia, Africa, and South America began to adopt the custom of April 1 hoaxing from their counterparts in Europe and North America. In this way, the tradition of April Fool's Day has now spread throughout the entire world. However, people in Asia, Africa, and South America primarily know April 1 as a day for media hoaxes, and individuals in these regions do not, by and large, engage in pranks at home and the office in the way that (some) people in Europe and North America still do.

Worldwide Spoof Ads

Despite the popularity of media hoaxes, advertisers mostly ignored April Fool's Day throughout the 20th century — with the one exception that stores would sometimes offer April 1 sales (accompanied by slogans such as 'You'd be a fool to miss these bargains!'). This began to change during the 1980s when a few companies (such as BMW) began to run spoof ads in British newspapers on April 1. By the 1990s, companies on both sides of the Atlantic had adopted the custom, noting the positive consumer response. (See, for example, the 1996 Taco Liberty Bell ad that ran in major American papers). Advertisers also realized that such ads had the potential to "go viral" and be talked about long after the ad campaign was over. In other words, they offered a great "bang for the buck."

(left) A typical April fool ad from early in the 20th century, 1930;

(right) One of BMW's first April fool spoof ads. It ran in 1983.

During the 21st century, the Internet has massively accelerated the popularity of April 1 spoof advertising, because of the ease with which videos and photographs can be shared online. It has reached the point now where hundreds of companies (and even organizations such as the US Army) release spoof ads on April Fool's Day. Some advertisers note that they actually feel compelled to participate in the custom, lest people think their brand lacks a sense of humor.

And just like April fool media hoaxes before them, April fool spoof ads have become a global phenomenon.

A spoof ad for Domino's canned pizza that ran in Japan - Apr 1, 2013

April Fool Free Zones

There are pockets of resistance to April Fool's Day, particularly in Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia. For instance, in 2001, Saudi Arabia's chief cleric, the Grand Mufti Sheikh Abdul Aziz bin Abdullah Al al-Sheikh, issued a fatwa decreeing that April Fool's Day was a form of organized lying practiced by unbelievers, and that Muslims therefore should not participate in the tradition. He acknowledged that many younger Muslims were beginning to adopt the custom, but said, "It is prohibited because lying is prohibited at all times and under all conditions."April Fool's Day has also made fewer inroads into Spanish-speaking countries where the Day of the Holy Innocents is celebrated on Dec 28. This is a day for pranks and media hoaxes, very similar to April Fool's Day. But even in these countries, it is becoming more common for the media and advertisers to create hoaxes for April 1.

The issue here is the placement of the apostrophe. Should the apostrophe be placed before the 's': as in, April Fool's Day. Or after the 's': as in, April Fools' Day.

Both spellings, it turns out, are correct. Or rather, neither spelling is demonstrably wrong. Valid arguments can be made for both. So for the foreseeable future, we shall doubtless continue to see both forms used.

However, "April Fool's Day" is the more popular spelling, and arguably has the better case for being correct, which is why that's the version used here on the Museum of Hoaxes. But let's review the arguments for both options.

Proponents of this spelling point to All Fools' Day, which is an alternative (now archaic) term for the celebration. Because All Fools is clearly plural, we might assume that April Fools is also so.

A number of authorities, including Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Macmillan Dictionary, Encyclopedia Britannica, and Wikipedia use this spelling.

For instance, the term could refer to the April Fool who becomes the victim of a prank. Or perhaps it derives from the cry of "April Fool" by a prankster, after a prank succeeds. Or perhaps it denotes the April Fool (that mythic character dressed in a multi-colored tunic and horned hat) who serves as the primary symbol of the day everywhere except in French-speaking countries, where a fish serves as the symbol.

An analogy could also be made with Mother's Day and Father's Day, both of which take a singular form. If they refer to a single mother and father, why shouldn't April Fool's Day refer to a single fool?

However, the strongest argument for "April Fool's Day" comes from an examination of the historical evolution of the phrase, which suggests that the April Fool was originally intended to be singular.

During the eighteenth century and into the first half of the nineteenth century, the April 1 celebration was usually called All Fools' Day. Or people would speak more long-windedly of the "custom of making April fools" on the first of April.

It was only in the mid-nineteenth century that the phrase "April Fool Day" regularly began to appear in print. (A few earlier instances of it can be found). But in this early usage, the phrase was almost always written without any 's' at all, as a singular word, no apostrophe anywhere.

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, "April Fool Day" rapidly became the preferred usage, eclipsing All Fools' Day. But simultaneously, over the course of that half century, an 's' began to be appended to the word 'fool' more often, until, by the dawn of the twentieth century, the phrase had transformed into "April Fool's Day".

It should be acknowledged that, from the start, there was very little consistency in the placement of the apostrophe. Confusion seemed to reign. Some late nineteenth-century writers spelled the phrase "April Fools' Day," doubtless influenced by the precedent of All Fools' Day. And some writers covered their bets by using a variety of spellings (April Fool Day, April Fools' Day, and April Fool's Day) all in the same article.

But overall, it seems clear that the phrase "April Fool Day" evolved into "April Fool's Day," and that "April Fools' Day" was always a relatively minor variant. For example, if one does a word search in the historical databases of the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, and Washington Post, one finds that between 1880 and 1920 "April Fool's Day" had already become the preferred spelling, appearing 130 times in those years, versus a mere 36 appearances of "April Fools' Day" and another 36 uses of "April Fool Day".

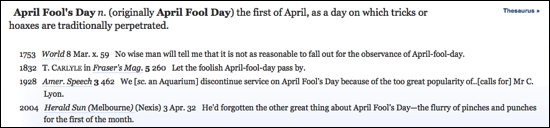

Among word authorities, the Oxford English Dictionary lists "April Fool's Day" as the correct spelling, citing the precedent of "April Fool Day". It's worth noting that the OED appears to be the only dictionary that offers a justification for its spelling of the celebration. Other dictionaries simply list a spelling, without explaining how or why they chose it.

The Oxford English Dictionary's listing for "April Fool's Day"

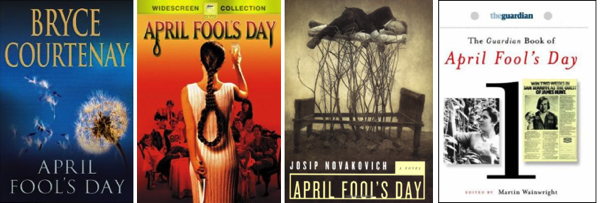

Throughout the 20th century, and into the 21st, "April Fool's Day" has consistently been the more popular spelling. A search for books and movies with the phrase "April Fool" in the title, shows that a majority use the "April Fool's Day" spelling. Notable among these titles is The Guardian Book of April Fool's Day (Aurum Press, 2007), which is the only English-language book ever published about the history of April Fool's Day, and therefore holds some weight as an authority on the subject.

On the other hand, one suspects that the continuing persistence of "April Fools' Day" may be due to the fact that, in the minds of some, this use of a hanging apostrophe must be correct precisely because it looks more awkward.

However, as noted at the beginning, neither spelling is demonstrably wrong. Therefore, whatever way one chooses to spell the phrase is ultimately a matter of personal choice. In fact, reverting to "April Fool Day" may be the safest choice, since it avoids the apostrophe controversy entirely.

Both spellings, it turns out, are correct. Or rather, neither spelling is demonstrably wrong. Valid arguments can be made for both. So for the foreseeable future, we shall doubtless continue to see both forms used.

However, "April Fool's Day" is the more popular spelling, and arguably has the better case for being correct, which is why that's the version used here on the Museum of Hoaxes. But let's review the arguments for both options.

April Fools' Day

The case for April Fools' Day rests on the assumption that the phrase refers to all fools in general. Therefore, to indicate the plural form, the apostrophe must come after the 's'. Proponents of this spelling point to All Fools' Day, which is an alternative (now archaic) term for the celebration. Because All Fools is clearly plural, we might assume that April Fools is also so.

A number of authorities, including Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Macmillan Dictionary, Encyclopedia Britannica, and Wikipedia use this spelling.

April Fool's Day

However, if the fool in April Fool's Day is singular, then, of course, the apostrophe has to be placed before the 's'. And proponents of this spelling offer a variety of arguments why April Fool probably is singular.For instance, the term could refer to the April Fool who becomes the victim of a prank. Or perhaps it derives from the cry of "April Fool" by a prankster, after a prank succeeds. Or perhaps it denotes the April Fool (that mythic character dressed in a multi-colored tunic and horned hat) who serves as the primary symbol of the day everywhere except in French-speaking countries, where a fish serves as the symbol.

An analogy could also be made with Mother's Day and Father's Day, both of which take a singular form. If they refer to a single mother and father, why shouldn't April Fool's Day refer to a single fool?

However, the strongest argument for "April Fool's Day" comes from an examination of the historical evolution of the phrase, which suggests that the April Fool was originally intended to be singular.

During the eighteenth century and into the first half of the nineteenth century, the April 1 celebration was usually called All Fools' Day. Or people would speak more long-windedly of the "custom of making April fools" on the first of April.

It was only in the mid-nineteenth century that the phrase "April Fool Day" regularly began to appear in print. (A few earlier instances of it can be found). But in this early usage, the phrase was almost always written without any 's' at all, as a singular word, no apostrophe anywhere.

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, "April Fool Day" rapidly became the preferred usage, eclipsing All Fools' Day. But simultaneously, over the course of that half century, an 's' began to be appended to the word 'fool' more often, until, by the dawn of the twentieth century, the phrase had transformed into "April Fool's Day".

It should be acknowledged that, from the start, there was very little consistency in the placement of the apostrophe. Confusion seemed to reign. Some late nineteenth-century writers spelled the phrase "April Fools' Day," doubtless influenced by the precedent of All Fools' Day. And some writers covered their bets by using a variety of spellings (April Fool Day, April Fools' Day, and April Fool's Day) all in the same article.

But overall, it seems clear that the phrase "April Fool Day" evolved into "April Fool's Day," and that "April Fools' Day" was always a relatively minor variant. For example, if one does a word search in the historical databases of the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, and Washington Post, one finds that between 1880 and 1920 "April Fool's Day" had already become the preferred spelling, appearing 130 times in those years, versus a mere 36 appearances of "April Fools' Day" and another 36 uses of "April Fool Day".

Among word authorities, the Oxford English Dictionary lists "April Fool's Day" as the correct spelling, citing the precedent of "April Fool Day". It's worth noting that the OED appears to be the only dictionary that offers a justification for its spelling of the celebration. Other dictionaries simply list a spelling, without explaining how or why they chose it.

The Oxford English Dictionary's listing for "April Fool's Day"

Throughout the 20th century, and into the 21st, "April Fool's Day" has consistently been the more popular spelling. A search for books and movies with the phrase "April Fool" in the title, shows that a majority use the "April Fool's Day" spelling. Notable among these titles is The Guardian Book of April Fool's Day (Aurum Press, 2007), which is the only English-language book ever published about the history of April Fool's Day, and therefore holds some weight as an authority on the subject.

Hanging Apostrophes

It's very likely that the popularity of the spelling "April Fool's Day" has nothing to do with the historical precedent of "April Fool Day." Instead, it probably derives from a widespread dislike of hanging apostrophes. People feel that they look awkward and avoid them whenever possible.On the other hand, one suspects that the continuing persistence of "April Fools' Day" may be due to the fact that, in the minds of some, this use of a hanging apostrophe must be correct precisely because it looks more awkward.

However, as noted at the beginning, neither spelling is demonstrably wrong. Therefore, whatever way one chooses to spell the phrase is ultimately a matter of personal choice. In fact, reverting to "April Fool Day" may be the safest choice, since it avoids the apostrophe controversy entirely.

There's been a great deal written about April Fool's Day. Every year for the past 100 years, whenever the day rolls around, newspapers and magazines have been producing articles about the history and customs of the celebration. Unfortunately, most of what's been written is not very good. The same small nuggets of information (and generous heapings of misinformation) are repeated uncritically over and over again.

To find better analyses of April Fool's Day, one needs to turn to folklorists, who have produced the bulk of the few serious studies of the celebration that exist.

Listed below is the best of the bunch. It's arranged in chronological order, to make it easier to see the most recent studies.

To find better analyses of April Fool's Day, one needs to turn to folklorists, who have produced the bulk of the few serious studies of the celebration that exist.

Listed below is the best of the bunch. It's arranged in chronological order, to make it easier to see the most recent studies.

- Brand, John. (1853). Observations on Popular Antiquities of Great Britain. A new edition, revised and greatly enlarged by Sir Henry Ellis. Henry G. Bohn: 131-141.

- Dickens, Charles Jr. (1869). "All Fools' Day." The Gentleman's Magazine. 2: 543-548.

- Lemoine, Jules. (1889). "Le poisson d'Avril en Belgique." Revue des Traditions Populaires. 4: 227-30.

- Bolton, H. Carrington. (1891). "All-Fools' Day in Italy." The Journal of American Folklore. 4(13): 168-170.

- Walsh, William S. (1897). Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities. J. B. Lippincott Company: 58-62.

- Pitre, Giuseppe. (1902). Curiosita di Usi Popolari. Catania.

- "How April Fool Originated and Some Famous Pranks," (Mar 31, 1912). The New York Times.

- "April." (1927). in E. Hoffmann-Krayer and Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli, eds. Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens, Vol I. Walter de Gruyter: 555-67.

- Wight, John. (1927). "April Fools' Day and Its Humours." Word-Lore. 2: 37-40.

- Opie, Iona, and Peter Opie. (1959). The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. Clarendon Press: 243-248.

- Laliberte, Monique. (1980). "Le poisson d'avril." Culture & Tradition. 5: 79-89.

- Dundes, Alan. (1988). "April Fool and April Fish: Towards a Theory of Ritual Pranks," Etnofoor (1). p.4-14.

- Santino, Jack. (1994). All Around The Year: Holidays and Celebrations in American Life. University of Illinois Press: 96-101.

- Beyst, Rene. (1995-1996). "Even ernstig over 1 April."

- Harder, Manfred Boje. (1999). Der Globus von Europa.

- Favrod, Justin and Jean-Daniel Morerod. (2000). "Le poisson d'avril est ne d'un jeu de mot quelque peu douteux." Liberte.

- McEntire, Nancy Cassell. (Summer 2002). "Purposeful Deceptions of the April Fool," Western Folklore. 61(2): 133-151.

- Roud, Steve. (2006). The English Year: A month-by-month guide to the nation's customs and festivals, from May Day to Mischief Night. Penguin Books: 94-96.

- Wainwright, Martin. (2007). The Guardian Book of April Fool's Day. Aurum Press.

- Smith, Moira. (Dec 2009). "Arbiters of Truth at Play: Media April Fools' Day Hoaxes," Folklore. 120: 274-290.

Forum Posts

Subscribe

via Feedburner

All text Copyright © 2014 by Alex Boese, except where otherwise indicated. All rights reserved.